Can Government be a Companion?

Digital personal services, agents and making government useful

How could governments be more useful, and be felt to be more useful? I’ve long been convinced that part of the answer lies in new kinds of public institution that are data-driven, personalized and empowering, and help people navigate the difficult choices of daily life, going beyond consumerism to become more like a companion.

Over the last few years there’s been lots of progress in creating integrated platforms and protocols to streamline interactions with the state – in Britain, gov.uk is now very good for many transactions, and many places around the world from Hong Kong and Canada to Ukraine, Singapore and Mexico City, to New Zealand with its SmartStart, have impressive, integrated platforms combining hundreds of services.

But these are nearly all focused on frictionless transactions and nearly all are passive, drawing their thinking from commercial consumer services. They are at best reactive rather than proactive, ie anticipating needs and problems.

There are still surprisingly few examples of public services which support and empower citizens in a more continuous way, making full use of personal data and preferences and giving advice about choices: in other words services that are personal, pro-active and anticipatory, like a true companion.

At the moment most people would be happy with government that was merely competent. But what I describe here could be a healthy direction of travel, helped by the potential for AI agents to make recommendations, to seek out information, and to streamline underlying bureaucratic processes. Here are a few sketches of what that might mean.

HEALTH AND FITNESS: MYHEALTH

The first example is health, where it’s been obvious for a long time that if you were inventing the NHS now, you would design it, in part, as a platform, giving highly tailored, personalized guidance and advice to people about what they could do for their health as well as things like booking appointments and managing prescriptions.

My mentor, Michael Young, came up with some of the first ideas for what became NHS Direct and at Nesta, we did a lot of design work on future options, some with the NHS and the BBC. We labelled some of the underlying elements a ‘Health Knowledge Commons’ (and ‘Doctor Know’). But the key was the interface with the public. This would include the capabilities of an NHS app to bring together health records, appointments and interactions with the system. But there would also be: video material giving short-form advice on everything from diabetes to fitness; for some, a way to link in the personalized data of Fitbits and similar devices; a space or link to peer support networks for people suffering from different conditions and cancers; and access to the vast pool of online health advice with ratings to guide on the reliability of different sources. We imagined that the platform could also act as a prompter, not just a passive responder, making suggestions on everything from blood tests to new diet options.

The aim would be to tailor its styles of communication to individual preferences, using some of the logic of a TikTok algorithm. Even ten years ago this looked a likely direction of travel and technically it was entirely possible. But we couldn’t find the political will to implement it; the BBC pulled out when it became clear they wouldn’t be supported by the then (Conservative) government; and the NHS was struggling with the problems of its online initiatives around care.

More recently the NHS app has greatly improved, and work is happening on possible AI Health Coaches for digital health and social care. Other countries have impressive new services, Estonia’s unified digital health platform, for example, links the 98% of citizens with a digital ID to a digital health record, with 20% having their genome mapped which in time will need to more accurate diagnoses. These point to the different level of ambition that is now possible, and what a ‘companion NHS’ could look like making full use of late 2020s technologies.

FUTURE JOBS AND SKILLS: MYJOBS

A second field is skills and jobs. Everywhere people are fearful that AI will destroy jobs and livelihoods. A basic duty of government should be to help them navigate their way to new jobs and skills.

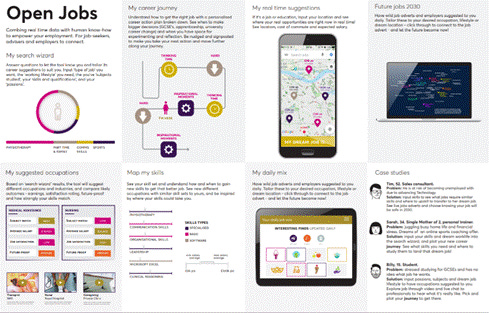

In my last job at Nesta we created prototypes of many of the elements, which we thought would be needed everywhere in the near future. That included gathering as much data as possible about current jobs, their skills requirements, pay levels and geography; good forecasts of where jobs are likely to grow or shrink and skills demands will grow and shrink; and then using these to shape navigation tools so that a 15-year-old in school or a 55-year-old who has just lost their job can see the best pathways, the most plausible new skills which could get them into a decent well paid job in the future (we called this Open Jobs and launched many of the elements separately too).

We weren’t able to persuade government in the UK to act on this partly because the task cut across government departments which aren’t good at collaborating. No-one owned the problem. But other countries have moved ahead. Singapore’s SkillsFuture is a prime example, and there are impressive initiatives in Canada, Australia and several Scandinavian countries. Bangladesh created NISE - a ‘national intelligence for skills, education, employment, and entrepreneurship’ collective intelligence system – and has now spread this to other countries.

As the UK introduces a lifelong learning entitlement in 2027, I hope that will be the prompt to create something better to guide people in using it, combining the capability of Co-Pilots and other AI assistants to act as supportive guides and coaches to help individuals of all kinds make decisions about their priorities. The slow pace of action in this space is striking, however: a combination of institutional silos, stunted political imagination and lack of technical capacity within governments.

SINGLE PERSONAL ACCOUNTS; MY MONEY

A third example is the personal account. This was the subject of a study I oversaw at the Cabinet Office in the early 2000s. The idea was that there should be a streamlined account for all financial transactions with government: taxes, benefits, licenses, fines, student loans and more. At the time all had entirely separate systems, with separate procedures, identification, protocols and communications.

There would be obvious savings from streamlining and simplifying in a single platform or at least with standardised protocols. But there was also the potential to build on this by enabling the state to lend money secured against future earnings – whether for student loans or first mortgages. This offered a route to a radically transformed welfare state that could use money much more efficiently for progressive ends. It would make it much easier, for example, to introduce a capital entitlement for young people (eg £10k or £20k at 18 for specified purposes), low interest loans and more.

Other countries moved towards personal accounts, including Singapore (through MyPass) and Denmark (through Nemkonto, a designated account). The UK didn’t, and we failed to convince the leading politicians who at the time were spending astronomical sums on systems within individual departments (many of which didn’t work well) and didn’t really get the idea that the strength of digital technologies comes from linking things up through simpler, shared systems. This essential lesson of the digital era is often missed by politicians and civil servants who instead commission elaborate, sometimes-Byzantine solutions that work well for vendors but less so in terms of results. But it’s not too late for government to make this a transparent, useful way to make peoples’ lives easier.

There are many other examples of direct engagement between national governments and citizens around the world. They include India’s Aadhaar and its standardised payments systems (part of the India Stack). There’s Brazil’s Drex digital currency and Pix payment system (which implements the idea of ‘central banking for all’, proposed for the UK more than a decade ago).

Other kinds of more direct interaction with citizens are returning in many countries. Mexico has an army of 20,000 officials visiting households, ‘Salud Casa por Casa’ (Health House by House). China and Korea have sophisticated, personalised anti-poverty strategies: all are examples of states using the power of 21st century technology to have a much more direct interaction with the citizen.

The dominant commercial platforms will not always be favourable to such activism on the part of the public sector. But the smart governments realise that they should be using the full power of digital technology to better serve their citizens directly, alongside tools that make it easier to link up with commercial services.

PLACE; MYNEIGHBOURHOOD

A final example could be place. Why not create a comprehensive platform, shared with local authorities, that provides easy access to the key plans and decisions affecting neighbourhoods? This would be organised as a mesh, a collaboration of national and local. It would allow you to see any planning applications for your street or area. It would streamline consultations and engagement over options. It would allow planning to break free from the deficiencies of the public meeting where the loudest mouths predominate, enabling people to make proposals and get feedback. It’s odd that there are various private neighbourhood sites like NextDoor, and some planning tools (including Planning Portal, UK Planning Gateway and others). But, again, none with the universality and simplicity that’s needed.

The virtues of simplicity

One of the great lessons of the digital era is that the right kinds of simplification and standardisation can pay off greatly. This was the insight of the Internet itself, and of the World Wide Web, and more recently of initiatives around Digital Public Infrastructures. Each of the examples described above aims to radically simplify the primary interface with citizens in order to orchestrate a much wider variety of options, services and sources of information, making it possible for government to be more like a companion alongside frictionless transactional services.

Each also aims to use the many possibilities of agents (some discussed here), potentially leading to more TikTok like public services (combining personalised algorithms and push communications) guiding on issues like financial literacy, pension choices or education.

There are many practical issues – how to support the minority still digitally excluded; how to handle procurement, preferably to encourage domestic providers; how all the data generated is protected and used. In most cases the implementation will need to be done by arms-length agencies or teams, with one foot inside government and one foot outside, free from unhelpful bureaucratic constraints. But this is a plausible and desirable direction of travel, and it could help with the bigger challenge facing all bureaucracies: how to simplify their processes and reduce the cognitive load on citizens and small businesses (UK government often seems determined to do the opposite, whether in tax or welfare) while also making the most of collective intelligence to guide difficult choices.

So far, in the UK at least, there have been few hints of these next generation public services. But they are doable. They would be useful. They would save money and time. And they could be very popular.

If Govt wants to be a 'companion', stop using AI dross that can't answer the real questions that humans want answered. Provide human contact on a telephone, because humans CAN answer the questions that AI fail to answer. AI in customer service' is completely useless.

Wasn't the UK leading the world in online cross departmental digital services ten or so years ago until deparmental silo mentality saw it all shut down. What do you do when the biggest impediment to online joined up governement is ........ government. Any signs that Labour are better (sure early days) than the the austerity/small government/neoliberal approach from the previous government. Despite his record on education/Brexit/eye sight testing Dominic Cummings does have interesting thoughts on government reform including how to recruit capable people into government to implement these projects.