Strength without weight

Seeking lightness in the design of new institutions and reform of old ones

The most miserable places on the planet are the ones without competent, accountable and ethical governments. But even in the happier places, too many public institutions weigh heavily on the public they exist to serve and are too slow, unresponsive and attached to opaque processes and rules.

The dominant metaphors used to think about government are equally heavy. We talk of ‘building’ institutions. Consultancies propose elaborate pyramid-like organograms, weighing down on the people at the bottom. The public are more likely to imagine government as a monstrous Leviathan (Hobbes), a mysterious castle (Kafka), or a vast machine, than as a friend or servant.

Ideas of lightness and light provide an alternative and may be more useful for designing the next generation of institutions. In this piece I explore what that might mean - and how values of lightness, openness, speed and flexibility are already being embedded into new institutions across the world (including the many now being documented for the UNDP’s Istanbul Innovation Days) and how these could be guides for more effective, and likeable, governments in the future.

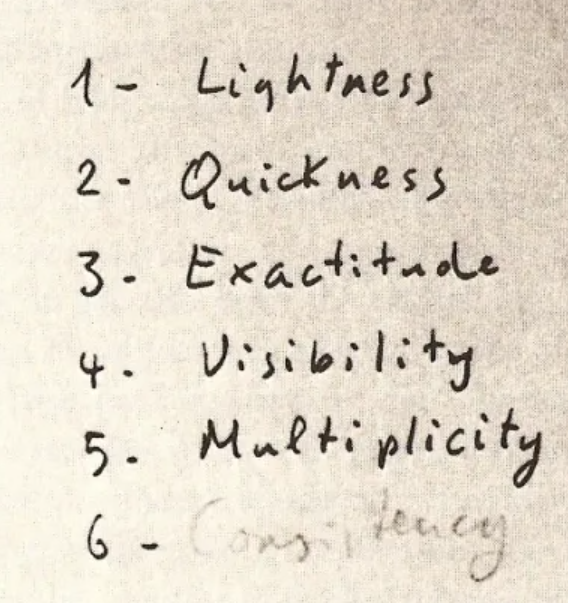

Governments don’t often learn from literature or materials science. But these provide some useful starting points. A particularly fertile literary inspiration is ‘Memos for the Millennium’, written by the Italian novelist Italo Calvino over forty years ago. His memos start with lightness, and then move onto quickness, exactitude, visibility, multiplicity (and potentially consistency) as guides to the spirit of the age, and they perfectly capture much of what’s needed in government now.

Another useful source is architecture. Many architects have sought lighter, more organic structures which not only look far less heavy than traditional classical, modernist or post-modernist architecture, but also use far less material weight. The Japanese architects Tadao Ando, Kengo Kuma, Shigeru Ban and Takaharu Tezuka, are examples, each in different ways trying to escape from the tyranny of walls, emphasising instead minimal structures, wide windows, a sense of movement and ubiquitous light, with works that make even concrete seem light (Ando) or create cathedrals out of cardboard (Ban).

A comparable retreat from weight has happened in materials science which has given the world not just graphene (pictured below and now increasingly present in everyday products like shoes) but also other materials, like carbyne, that combine lightness with extraordinary strength. These distribute stress more evenly than traditional materials, using lattice structures partly inspired by ones found in nature such as in bones and shells.

These inspirations suggest a direction of travel for governments, and how they could become lighter, more agile and adaptive. They point in a very different direction to the chainsaw, scorched earth approach of Elon Musk, or the prescriptions of Project 2025, one of the blueprints for the Trump administration, which commits to ‘dismantle the administrative state and return self-governance to the American people’, but primarily focuses on how to radically cut spending and activity, and return to an 18th century model of small government, rather than offering proposals which look to the future. Instead, what I describe here is a search for maximum strength and minimum weight, making the most of 21st century technologies and ideas.

LIGHTNESS

Some public institutions should be slow and heavy. Constitutions shouldn’t change from year to year. Parts of government should take a very long view - from pensions policy to infrastructure planning.

But for others lightness is a good general design goal that prompts us to ask: what is the minimum necessary bureaucracy, the minimum necessary weight of structure, needed to achieve goals?

It will not usually be zero. But often layers can be removed; as can organisational walls, roles and processes. As in architecture and materials, there are usually options available that can achieve less with more. And it is always useful to do exercises that imagine – if we had to cut half the budget, or half the roles – what would we do?

As I’ll show these lead to some of the new design ideas that TIAL has been developing: putting generative shared intelligence at the heart of institutions; organising in meshes rather than pyramids; and pursuing radical simplicity wherever possible.

These methods and mindsets matter because all bureaucracies tend to grow, creating new rules or processes for every anomaly. Legal minds gravitate in a similar direction – constructing general rules or laws in response to crises, scandals and problems. Public inquiries typically conclude with dozens of recommendations for new procedures and politics often encourages a mushrooming of legislation in response to lobbying.

The results are stunning. The Regulatory Studies Centre at George Washington University estimates that US federal regulations have grown from 20,000 pages in the early 1960s to over 180,000 today, with federal government imposing 12bn hours of compliance work onto citizens (35 hours per person, up from 27 hours in 2001).

Similar trends can be found elsewhere - in Germany the text of laws has grown by 60% over the last three decades. And across Europe the multiplication of slightly different rules in different countries remains a major constraint on growth, a heavy de facto tax on doing business (amplified in some countries by the survival of extraordinary anachronisms, like the notaries in Italy who have to read out lengthy contracts before they are signed). Here we see how easy it is to put on weight and slip into a bureaucratic and legislative obesity crisis that gets in the way of public value.

Fortunately, there are lots of examples of potential counter-measures: from Portugal’s SIMPLEX programme to the UK Red Tape Challenge which crowd-sourced ideas on culling useless rules; and from south Korea’s ‘Regulatory Guillotine’ in the late 1990s to waves of regulation culling in Australia and New Zealand at a similar time.

The best approaches combine fresh outside perspectives with deep inside expertise (there’s no shortage of half-baked ideas on what needs to be done, and no shortage of incumbents convinced that change isn’t needed - it’s vital to get beyond both).

Some have rationed rules and laws, like a diet or a ‘bureaucratic budget’. Canada for example has followed a ‘one for one’ approach - one rule cut for any new one introduced. And in the 2000s the Netherlands targeted a 25% annual cut in red tape for business (later copied in other countries).

Governments can also aim to lighten the cognitive load on citizens when designing any policies (Australia’s Treasury has long been a good example of this, the UK a particularly bad one, with ever more complex tax and benefits rules that work on paper but make life difficult for citizens and businesses). ‘Once only’ digital models are also a good way to cut cognitive loads, so that you only have to tell government once when, for example, you move home or someone dies (though experience over the last 20 years shows that they’re quite difficult to implement).

Keeping weight down requires regular culls to trim back contracts, compliance requirements, reporting and more, which otherwise tend to spread. And weight loss programmes will always involve more efficient triage and risk assessment rather than blanket processes. But research suggests that cuts aren’t always bad for society or the economy. Sometimes they can be positive, especially where taxes weigh heavily on the poor, and spending is influenced by wealthy interest groups.

The general point is that we need government to think like gardeners who know that regular weeding, trimming and pruning are essential for helping gardens to flourish. And we need governments that are fit not fat, agile not sluggish.

RADIANCE AND VISIBILITY

A second design principle has more to do with light than lightness. Recent decades have seen the spread of institutions that prioritise radiance as a goal: making knowledge, data and information visible and widely available. These radiant organisations are ones that provide data, knowledge insight to whole systems, usually (but not always) without payment. They can be found in all sectors and they have become increasingly important, a vital part of public value.

Examples range from Google providing free search and much else, to Open AI and Deepseek offering LLMs to the world. They include the IPCC providing the world with analyses of climate change and government statistical services providing reliable data for economies and societies; organisations providing open data and indeed the whole science system which provides knowledge freely and openly.

Recent examples show how this idea could be extended. One of my favourites is the International Solar Alliance which supports global action to implement solar power - a good example of what I call ‘intelligence assemblies’ that combine data, know-how, predictive models and tacit knowledge to support action at scale. The ISA is particularly interesting because of its focus on practice, and like other radiant organisations it helps a much larger system to make decisions and act, not through command, force or finance but through the power of information.

Yet many fields still lack equivalents - from jobs and skills to plastics to care. For example, no societies have institutions like the ISA to support fields like eldercare with data, insights, training, tech adoption support and sharing of tacit knowledge, even though these can have obvious benefits for productivity, growth and policy success. Perhaps most surprising of all is the fact that AI itself still lacks a radiant organisation to help the world make sense of its possibilities and challenges.

OPENNESS

These examples draw on a third useful design principle: seeking maximum openness as a default. This isn’t just about transparency and bringing sunlight into the darker recesses of the state, valuable as that is. Nor is it just about open data: again, hugely valuable through collaborations like the 77-country strong Open Government Partnership which links national initiatives like the US Open Data Project.

Instead it goes further by building openness into the very DNA of new institutions through institutional designs like open network models that use protocols to connect multiple networks.

This was the founding idea of the Internet, nearly 60 years ago, and it points to options to radically reshape governance for everything from identification to education to finance. Beckn is a prime example of this new generation of OTNs (open transaction networks), a model which is being applied to fields like energy, though these concepts are still barely understood in many governments.

Mutual openess can also help institutions to thrive. As individuals we often benefit from having a coach, a mentor or just a friend who can give us candid advice. Many public institutions also perform better if they are complemented by ‘mirror institutions’, which audit, assess, scrutinise, coach and challenge them.

There are many examples: the Office of National Statistics in the UK sits alongside an Office for Statistics Regulation which scrutinises it and keeps it honest (and steps in when, as now, a crisis of credibility has hit the ONS). Efficiency units and teams play a similar role, a partly external pressure to cut waste and efficiency, using benchmarks and analytics to spot patterns that may be invisible to the institution itself. ‘Red teams’ do a parallel task in cybersecurity and policy design, mimicking the thinking of an attacker to help make institutions more resilient.

All are a reminder to think of institutions not as standalone entities, but rather as thriving within systems that combine cooperation and competition, coaching and challenge.

MULTIPLICITY AND MESHES

Much of the organisational innovation of recent decades has encouraged multiplicity - more variety, personalisation and diversity in place of ‘one-size-fits-all’. The promise of the Internet was that, through common protocols, far greater variety would be possible, and that is part of the logic of open network models too.

For anyone working on institutional design the value of these kinds of ‘meshes’ that are similar in spirit to materials like graphene soon becomes apparent. They weave together multiple tiers of government, and multiple partners, but in flexible and resilient ways: combining both vertical and horizontal integration (see my overview of the methods for ‘whole of government’ action).

Buurtzorg is an example in care, which describes itself as like an onion, with the lightest possible coordination to connect its thousands of carers, organised in cells. Bangladesh’s NISE is another great example, a collective intelligence platform to help people navigate new skills and career options.

Even more ambitious are the technology stacks, like the India Stack which provides a framework connecting communications, identification and payments through APIs and digital public goods. Europe is now thinking of copying this as part of its strategy to achieve independence from the US platforms, with work on a Eurostack, and some governments are already developing their own stacks, like Singapore’s GovtTech Stack (SGTS).

QUICKNESS (AND, SOMETIMES, SLOWNESS)

Perhaps the most common complaint about bureaucracies is that they are often so slow, tied up in their own processes and red tape. This is why they fall so far behind fast-moving technologies, or struggle to respond to disasters.

But there are many examples of speed: some were visible in the early stages of the COVID pandemic as governments rapidly reinvented education, welfare and more; they can be seen in wars, as armies relearn the virtues of extreme speed and governments reshape manufacturing to provide flows of munitions (something Europe is leaning into fast, learning from examples like the ones documented in the classic ‘Freedom’s Forge’ by Arthur Herman which describes how the US government dramatically overhauled manufacturing and R&D during WW2).

There is now a repertoire of ‘fast institutions’ with a very short life span that can be used to handle a crisis or a disaster. These benefit from ready-made, digital templates - so that a temporary institution can be created immediately with clear governance and decision-making procedures (the UNDP’s handbook on recovery institutions and the World Bank’s GFDRR templates are examples). Another vital element is networks of expertise on tap that can be quickly mobilised.

As Leo Quattrucci shows in his recent analysis of procurement and AI agility has become ever more essential to the everyday work of governments as well, as the pace of technological change accelerates, not least if governments want to avoid waste in the 12% of GDP in the OECD countries that goes through public procurement.

But there is also a need for opposite qualities: slow institutions that can take a long view or even a generational perspective, such as foresight teams, futures institutes, future generations commissioners and even actuaries, as well as infrastructure planning, pensions and climate action. Often governments do fast the things that should be done slowly - that require time to deliberate, digest and decide - even as they do too slowly tasks which should be done fast.

EXACTITUDE (AND SIMPLICITY)

Recent years have seen some trends to exactitude: more precise goals, metrics and use of data (though sometimes with perverse consequences ‘ meeting the target but missing the point’).

While some institutions focus on coordination and whole systems, others are best ‘laser-focused’ on specific tasks and designed to avoid any distractions.

Exactitude also connects to the related goal of requisite simplicity. Clever people can often design elaborate answers to problems, not least because problems often are very complex.

But overly complex plans often fail in implementation. Simple ideas work better, or complex plans that can be broken down into simple ones. It’s easy to over-estimate the absorptive capacity of people and systems - life is busy and attention span is limited. Simple, sticky and memorable concepts are very helpful as ideas move into action, which is why, when dealing with complex issues, it’s always wise to strive for what Oliver Wendell Holmes called the ‘simplicity the other side of complexity’.

This is often difficult for progressives - whose instinct is to ask every policy and institution to contribute to solving all of society’s problems: for schools to deal with mental health or social inequality; for public investment contracts to include multiple clauses about equity, carbon emissions, and more. These are all worthy: but their net effect is often to make it harder for these policies and institutions to succeed. Better to keep programmes, and contracts, as simple as possible.

Sometimes, however, simplicity and exactitude point in opposite directions. Much of China’s recent success stems from the use of quite ambiguous central directives which leave plenty of space for local discretion. Indeed, in any context in which local knowledge is superior to central knowledge, this kind of ‘directed improvisation’ (to use Yuen Yuen Ang’s phrase) works better than precise commands: simple guides that leave people on the ground to work out the complexity.

Getting beyond traditional trade-offs

These various ideas that are evolving around lightness, radiance, meshes, quickness and multiplicity, point to very different kinds of government from the ones which grew in the 20th century, the monolithic bureaucracies to be found in the big buildings of capital cities.

They also suggest possible answers to the trade-offs that face anyone trying to design a new institution or redesign an old one.

· Distributed or decisive? The more distributed power is, the less it may be possible to solve difficult problems decisively.

· Inclusive or fast? The more inclusive and consultative the institution, the slower it is likely to be.

· Integrity or innovation? The more focused an institution is on process integrity in order to cut waste and corruption, the less autonomy and innovation there will be.

· Control or creativity? The more strictly finance is controlled the less scope there will be for positive risk.

Some of these trade-offs are unavoidable. But the promise of new tools and new ways of thinking is that they can partly shift and even resolve these trade-offs. The more there is shared intelligence, shared standards and protocols, the easier it may be to reconcile these opposites – shifting the curves in the language of economics. The better designed the meshes, the less need there is for heavy hierarchy. In other words these new approaches potentially make it easier to be distributed and decisive, inclusive and fast, honest and innovative, controlled and creative.

Learning lightness

The world has many wonderful schools of architecture and business design. But there are no equivalents for institutional design and institutional architecture, and no centres for exploring options like this and specifically what works best for what tasks and in what contexts (this is the problem that TIAL was set up to address).

Our hope is that a more lively interplay between ideas, practical examples and design can help to grow a field with common languages, concepts and ideas - and a better response to the challenges of distrust and inefficiency than the alternatives of either thoughtless destruction on the one hand, or defense of the status quo on the other.

The UNDP’s Istanbul Innovation Days showed what this means in practice: the remarkable amount of creative innovation happening around the world, on topics ranging from heat to the management of time, data to energy, care to democracy, and the options for the years ahead.

IID confirms a convergence of thought and action around some of the ideas described here. But these are often unfamiliar to people who have spent their lives around government. My hope is that before long they become obvious, a new common sense, and that we learn again that government can have strength without weight.

A final quote comes from Italo Calvino who wrote that he had ‘tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities; above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language… I have come to consider lightness a value rather than a defect….every branch of science seems intent on demonstrating that the world is supported by the most minute entities, such as the messages of DNA, the impulses of neurons, and quarks, and neutrinos wandering through space since the beginning of time…it is software that gives the orders, acting on the outside world and on machines that exist only as functions of software and evolve so that they can work out ever more complex programs’.

Design and architecture styles are products, and also influencers, of their social eras. But they are still ephemeral. Just at a slightly faster pace than government in Stewart Brand's Pace Layers.

Phrased differently: when mid-century modern finally ends, do we need to redo all governance again?

A demand for lightness reflects more of the cumbersome effects of complexity on comprehension and change rather than an inherent value in itself. I would argue complexity is not the problem, and oversimplication -- i.e., reductionism -- is not a helpful answer.

Especially since we learned about Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety, aka the First Law of Cybernetics, back in the birth of mid-century modern:

“The complexity of a control system must be equal to or greater than the complexity of the system it controls.”

I.e., a stable system needs as much variety in the control mechanisms as there is in the system itself. Oversimplifying rules for cognitive convenience in the face of the natural complexity of the world goes hand-in-hand with authoritarian states. Do we want that?

Pretending complexity doesn't exist for the convenience of enfeebled minds and our resistance to change is not the solution. There are existing examples of more agile governance in practice at smaller scales yet: the FDA’s Digital Health Software Precertification(Pre-Cert) Pilot Program, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority’s use of regulatory sandboxes for fintech innovation, the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team’s use of iterative policymaking, and Estonia’s e-governance initiatives leveraging agile principles to deliver government services.

One of the key aspects includes governance being more proactively involved in the regulated businesses themselves. This raises major risks of regulatory capture. However, the alternative is regulation that is completely blind and ignorant to the concerns and internal affairs of the dynamic organizations they are authorized to regulate.

Governance needs to definitely shed the old where necessary. But it also needs a freer hand to experiment and make the fail-fast-and-learn mistakes that we much more readily afford start-ups. Otherwise perfect is always the enemy of progress, and "perfect" will always evolve and be redefined as it interacts with an evolving broader world.